Imagine yourself as a loyal Cincinnati Reds fan on the evening of May 24, 1935.

You were one of the 20,422 who had paid a top dollar of $1.75 for a seat in Crosley Field at the corner of Findlay and Western avenues in the West End.

First of all, you would have been astounded by the size of the crowd in the ball park that held nearly 30,000. The average attendance was but 5,821 loyal fans in a year when they finished sixth out of the eight National League teams.

But that is not what happened that night in May at Crosley Field. What happened is something that you had likely never seen before and would stay with you the rest of your days.

As dusk fell on Cincinnati’s West End that evening, about 500 miles to the east in Washington, D.C., President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with his usual gusto, smiled for the cameras and flipped a switch which turned on the 632 lights that had been erected on poles at Crosley Field and set the ball park ablaze in light.

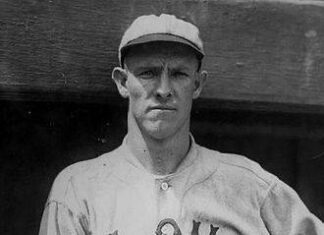

It was the first night game in Major League Baseball history. The Reds versus the Philadelphia Phillies. With the Reds ace pitcher, Paul Derringer, on the mound.

You likely would have been stunned by the sight of baseball being played at night, under the lights.

It was not the first time, of course. Since 1930, the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League played night games with a set of collapsible light stands that owner J.L. Wilkinson (no relation) had paid a pretty penny for and that the Monarch dragged around the Negro League ball parks so they could play night games everywhere.

But the lights were rather dim and, with the dominance of Major League Baseball in those days of segregated baseball, relatively few people got to see games under the lights.

But if you were anywhere in Crosley field that night in May 1934, you could see it all, clear as a bell.

You could see every pitch of the duel between Derringer and Phillies’ pitcher Joe Bowman, every ground ball fielded cleanly (there were no errors recorded by either team) and you could see the majesty of a deep fly ball hammered into the night sky.

A fly ball at night, wrote one scribe for a Cincinnati newspaper, looked like “a pearl on velvet.”

Plus there was the pre-game hoopla – a band concert, marching color guards from Norwood, two American Legion posts marching on the field, according to Redleg Journal, a 2000 book written by Reds team historian Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, a prolific author on Reds baseball.

The Reds ended up defeating the Phillies 2-1 in a game that took only one hour and 35 minutes to play – about half the time of the average Major League Baseball game today.

Crosley Field came close to not being the scene of baseball history that night.

When Larry McPhail, the general manager of the Reds, brought the idea to the other big league teams in early 1935, they were all opposed. Vehemently opposed.

McPhail was an innovator. The year before, he was the first general manager to use an airplane rather than a train to get his team from one city to another. He flew the Reds from Cincinnati to Chicago for a series at Wrigley Field.

When McPhail suggested night baseball, the other owners started tripping over themselves, trying to find excuses for why it wouldn’t work – the lights wouldn’t be bright enough; players and fans couldn’t see the ball; it was an undignified gimmick for a game that valued tradition.

McPhail and the Reds owner, Powel Crosley, kept pushing and, finally, the other owners agreed – but only to seven games, one against each of the other National League teams.

It worked like a charm.

When the other owners saw the turnstiles spinning at Crosley Field with fans who couldn’t take off work to go to day games, night baseball caught on fairly quickly.

The Reds drew an average of 18,620 fans to their seven night games that year. The day games drew a paltry average of 4,607.

No wonder it caught on throughout baseball. Except, of course, at Wrigley Field in Chicago, the ancient home of the Cubs. There, lights were installed in 1988 and the first night game was played there on Aug. 9 of that year.

McPhail eventually moved on to the Brooklyn Dodgers, where the Dodgers held their first night game at Ebbets Field on June 15, 1938. That just happened to be the same night that Reds’ pitcher Johnny Vander Meer did something that had never been done before and has never been done since – he threw the second of his back-to-back no-hitters. His first was four days before against the Boston Bees at Crosley Field.

Yes, baseball was a crusty game in those days, hidebound by tradition. And it still can be at times.

But, 84 years ago, a baseball visionary named Larry McPhail changed the face of baseball forever – but only by convincing team owners that there was money to be made.

Howard Wilkinson is 91.7 WVXU’s senior political analyst. His “Tales from the Trail” column appears on wvxu.org every Friday and gives a behind-the-scenes look at Wilkinson’s 45 years of covering the campaigns, personalities, scandals and business of politics on a local, state and national level.