(EDITOR’S NOTE: Kim Johnson alleges hospital workers missed her cancer — then covered up their mistake. Johnson is not only battling a deadly disease, but also a health system that went to extraordinary lengths to hide an error, her lawyers say. Following is a report shared by NBC News with The Ledger Independent and published in two parts. This is Part 2.)

‘Somebody’s got to stand up’

Johnson might never have learned what her medical records contained if it wasn’t for a nurse at Dr. Murley’s office. At a follow-up appointment, after it became clear that the delay in Johnson’s diagnosis might cost her her life, she said the nurse pulled her aside and offered some advice.

“She told me that Dr. Murley has never done this in her career, but that you need to seek legal help,” Johnson said. “When she said that I was like, ‘Gosh, this must be serious.’”

A lawyer representing Murley declined to comment and St. Elizabeth, the hospital she works for, said it’s the hospital’s policy not to comment on ongoing litigation.

“I had a lot of back and forth in my mind about whether I should do this or give them a pass,” Johnson said of filing the lawsuit. “I’m a Christian woman and this is just not something we do. But I feel like somebody’s got to stand up for people.”

In September 2016, Johnson sued the hospital that sent her the cancer-free letter and other medical workers involved in her care. Fleming County Hospital responded with a legal filing claiming that it had actually sent Johnson two other letters telling her the results of her mammogram were indeterminate and that she needed to come back for a follow-up screening within four months.

Johnson was baffled. She insisted she’d never seen the letters. Despite the disagreement, Johnson and Fleming County Hospital reached a $1.25 million settlement in April 2018 — enough to at least defray the significant cost of her ongoing cancer treatments. The hospital’s new owner, LifePoint Health, was not part of the settlement, and Johnson’s case continued against the for-profit hospital chain and other medical providers.

Johnson and her attorneys, Dale Golden and Laraclay Parker, said they would never have settled for that amount had they known what they would discover a year later: that the two follow-up letters appeared to have been created only after Johnson filed her lawsuit. That was the conclusion of Andrew Garrett, the digital forensics expert hired by Golden and Parker as part of the ongoing lawsuit against LifePoint Health.

Garrett, who was paid tens of thousands of dollars for his work on the case, trawled back-ups of the hospital’s electronic medical record system during a court-ordered site visit to check Johnson’s record at five points in time before and after the lawsuit was filed, as well as the audit trail of who accessed and altered the record.

His forensic report pieced together a timeline of events that showed how two hospital employees edited Johnson’s mammogram record three times within six weeks of her filing the 2016 lawsuit. These changes not only deleted records that supported Johnson’s claims of medical negligence, Garrett wrote, but also allowed the hospital to generate the fake letters that formed the basis of their defense.

Garrett’s report, which was filed as part of Johnson’s lawsuit, states that after Johnson’s mammogram in 2015, a radiology technician named Barb Hafer left a comment in the medical record stating that Johnson needed to return for a biopsy. However, according to Garrett’s report, the code she entered in the dropdown menu that dictates which notification letter is automatically generated and mailed to the patient was “NEG,” standing for “negative.” This explains why Johnson received the cancer-free letter.

For nearly two years, according to Garrett’s report, those notations remained in Johnson’s medical record. But that changed after she filed her lawsuit in late 2016.

A week after the suit was filed, according to Garrett’s report, a person who signed in under Hafer’s name accessed Johnson’s 2015 records and changed the mammogram code from “NEG” to “ABN,” standing for “abnormal.” A month later, that code was altered again, this time under the name of another radiology technician, Kristal Humphries, to retroactively direct Johnson to get a four-month follow-up. A third change by someone using Hafer’s login deleted her initial comment calling for a biopsy and replaced it with a comment to match the edits made under Humphries’ name, recommending a four-month follow-up.

“The changes to Johnson’s medical record were designed to hide the wrongdoing of Johnson’s medical providers and shift the blame to Johnson,” said Parker, Johnson’s attorney.

Lawyers for the hospital and other defendants, including Hafer and Humphries, have argued in court that the electronic medical record system in use at the time was “error prone and glitchy” and that the initial note calling for a biopsy in Johnson’s record was the result of Hafer getting her confused with another patient with the same last name. Although the hospital has not submitted its own expert report disputing Garrett’s findings, it has argued in legal filings that the audit trail cannot be relied on to prove his conclusions.

During a deposition last November, Hafer acknowledged that the audit trail appeared to show her making changes in Johnson’s record, but she denied doing so. Hafer also said she had no memory of getting Johnson mixed up with another patient and did not know how hospital lawyers came up with that theory. Humphries has not been questioned under oath since Garrett wrote his report showing edits made under her name. Neither Hafer nor Humphries responded to messages sent to them or their lawyers requesting interviews.

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of Johnson’s case, according to some experts, is that her lawyers were able to discover the alleged changes. Lawyers representing both hospitals and patients say it’s gotten easier to cover up medical mistakes since the advent of electronic recordkeeping systems. Previously, handwriting experts could often detect when medical staff made substantive changes in written notes.

Keris, the lawyer who specializes in defending hospitals in malpractice cases, said the back-end data stored in electronic medical record systems is remarkably complex, making any case involving an audit trail far more difficult and expensive for both plaintiffs and defendants.

“They’re horrible for malpractice cases,” Keris said of electronic medical record systems. “It’s very difficult to put together a chronology or timeline of events as to what occurred.”

In Johnson’s case, getting a hold of the complete audit trail of her records was an uphill struggle that required a court order as well as intricate knowledge of the hospital’s software and data storage systems — knowledge that many medical malpractice attorneys don’t have. And hospital lawyers have repeatedly disputed whether it’s even possible to track changes made to Johnson’s medical record — a claim that Garrett dismisses as “patently false”

“Every defendant fights to the death to keep you out of the system,” Garrett said. “They say it’s a fishing expedition, that it’s overly burdensome, that it’s intellectual property, that the data doesn’t exist.”

“What I have seen over the last decade in medical malpractice cases is staggering.”

An ongoing battle

Days after her cancer diagnosis, Johnson received the first of more than 50 rounds of chemotherapy through a port surgically implanted into a vein in her chest. She had her first of more than 40 radiation treatments soon after.

The cocktail of drugs turned her skin gray and her toenails and fingernails black. Teeth and clumps of dark brown hair started falling out.

“I was just a zombie,” she said.

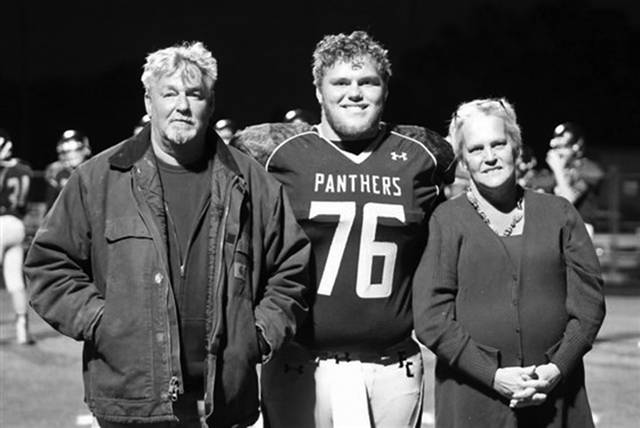

One day in the spring of 2016, she asked Delbert to shave the tufts of hair that remained on her head.

“It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done,” Delbert said.

They both went into the bathroom while their son Sam, who lived at home at the time, sat outside. He listened to his mother sob over the buzz of the clippers.

“She walked out, wiped a tear and said, ‘What do you guys want for dinner?’” Sam, now 21 and a welder, said over the phone from Arkansas. “She does not let cancer define who she is.”

More than five years after her diagnosis, Johnson is still fighting, both in court and outside of it.

Johnson’s doctors tell her she’s a walking miracle. “They can’t understand how I’m still here,” she said.

After discovering the alleged changes to her medical records in 2019, Johnson’s legal team filed motions to undo her original settlement, force Fleming County Hospital to rejoin the case and to demand further damages for the alleged effort to alter Johnson’s medical records.

The trial judge ruled they couldn’t undo the settlement unless Johnson repaid the money, which she says she needs to cover medical bills. The judge also dismissed Johnson’s conspiracy allegation, noting that there’s no statute under Kentucky law that allows patients to seek civil damages for falsified medical records. An appeals court upheld that decision in November, and now Johnson’s lawyers are appealing to the Kentucky Supreme Court.

Rather than dwell on the legal fight, Johnson, now 59, said she pours what energy she’s got left into taking care of her farm, the three children still in her care, and herself — a busy daily routine for someone who’s been battling cancer for half a decade.

Although the medications she takes sap her energy, Johnson wakes up at 5:30 a.m. to feed the horses, cows and chickens, before waking the kids, ages 6, 11 and 12, to get them ready for school. When she returns home, she starts her daily cancer regimen, informed by hours online reading the latest research and alternative treatments. She drinks 40 ounces of carrot juice, spends two hours in an infrared sauna and walks for 2 miles on a treadmill set up in what she and Delbert call her “she shed.”

“My life is pretty well occupied by cancer and the kids,” she said. “But I’m here to take care of them, so it’s important I do whatever it takes.”

Even though she’s beaten the odds so far, the cancer has continued to spread. Johnson had surgery to remove a new tumor from her neck in January, but doctors couldn’t get it all — it was wrapped around her jugular vein and a bundle of nerves. She worries the cancer doesn’t have far to go to reach her brain.

Johnson thinks often about her mother’s nearly decadelong cancer fight. She fears becoming a burden to the people she loves — a thought that’s all the more upsetting when she considers that all of this might have been preventable.

“What I worry about the most is the kids,” Johnson said. “If they just would have sent me for a biopsy, maybe I would have more time to spend with them.”