“Home is where the heart is.”

This endearing but hackneyed utterance comes to us as a survivor from the fog of millennia, but credit for its origin goes to Gaius Plinius Secundus, shortened to Pliny the Elder, a Roman author, naturalist, government official and military commander who lived 23-79 AD. For expressing all the sentiment attached to our individual places where we feel most content and happy, it is as good a definition as anyone has stated, thus its endurance through time.

Physical homelessness where people have no permanent structure in which to shelter is a terrible social problem that is much in the news. But the Pliny definition goes much deeper than a reference to a shelter from the elements. The emotional and spiritual aspects of life apply, and it is very possible to lose these elements of hominess and still have an edifice for physical refuge.

Properties that compose “home” in the Pliny definition include human, cultural and physical fixtures that combine to make ambience. All these are mutable and subject to change and loss. Humans are mobile creatures and often decide to make changes in location for a multitude of reasons. In such cases the heart must adjust and adapt to different conditions, or else the new home will be nothing more than a shelter.

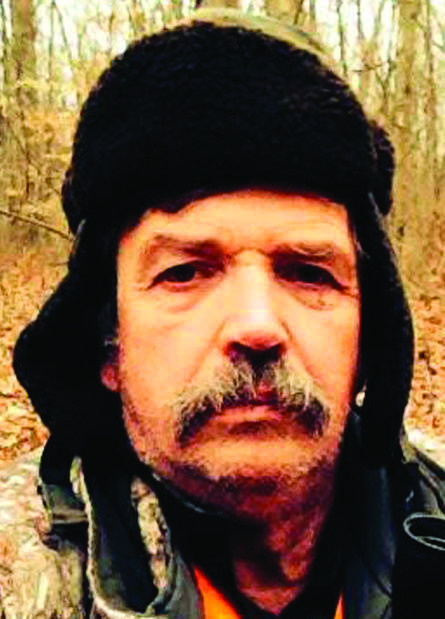

I have not been geographically mobile. I have moved to a new spot only once, and the new site had always been a second home. Peculiar to my circumstance was that much of the old home that came along with my condition is unique, but with its own keen cut of loss. Under the Pliny definition, one can become homeless even without ever losing access to a place and an edifice with the loss of too many or all of the attributes upon which his heart has fixed.

The home wherein my heart would lie most contentedly is gone beyond recovery. That would be the Cabin Creek of the 1960’s-74, when people with old neighborhood family names still farmed row crops from the narrow river bottoms at Springdale all the way to Ky. 57 in both creek valleys. The creek was a ribbon of clean potholes that county road departments had not drained while plundering for limestone, and spotted bass came from the river to them every spring as well as to the mouth every fall, and no person or corporate entity objected to fishermen gathering on the shore to fish for them.

We were beginning to see occasional deer in those days long before the mania of deer hunting drew armies of outsiders to invade our hills as precursors to the big business the sport would become, in time to transition hunting increasingly into an activity for the elite. You could hunt virtually anywhere in those days — the squirrels, rabbits, grouse and few quail coveys up and down the valleys had no economic value great enough to make access to them a marketable commodity.

It is indeed possible for one to live long enough to become an outsider in his own familiar place and to experience the helplessness of seeing his life inexorably stripped away in small parts until little or none of it remains. I call this phenomenon “outliving one’s own life.”

Readers will have noted that three of my columns last month had to do with memories. The onset of summer always puts me in a state of maudlin reflection. Maybe it is the somnolence that heat and the accumulation of verdure that lays a somber mood over the land and that this seizes into my mood.

History also contributes.

My father passed in mid-June and Springdale ended in dust and noise in early July. It was during these days leading up to Independence Day 45 years ago that my mother and I spent the final few days of that doomed village as its last residents. Since her passing last fall I have become the last person who lived in Springdale.

It is a continuous human struggle to maintain constancy in an inconstant world and to experience the comforting recurrence of the familiar. We attain this best in small things that become of paramount importance: the bloom of generations-old bulb flowers in the backyard, the coming of squirrels to cut in revered hickories, or the pre-spawn bass bite.

Interruptions in these rituals are at the least unsettling, sometimes shattering. Most disturbing of all is the realization that most of us lack the power to insure that these small glories are always a part of our individual slices of forever.

Pliny’s definition means that “home” is what we can make out of the assets we can gain and hold, the holding being the most difficult part because of the destructive character of change and time, which drives it. As we age, avoiding “homelessness” becomes an increasing challenge over which we have little control.